William Leefe Robinson / The Pilot

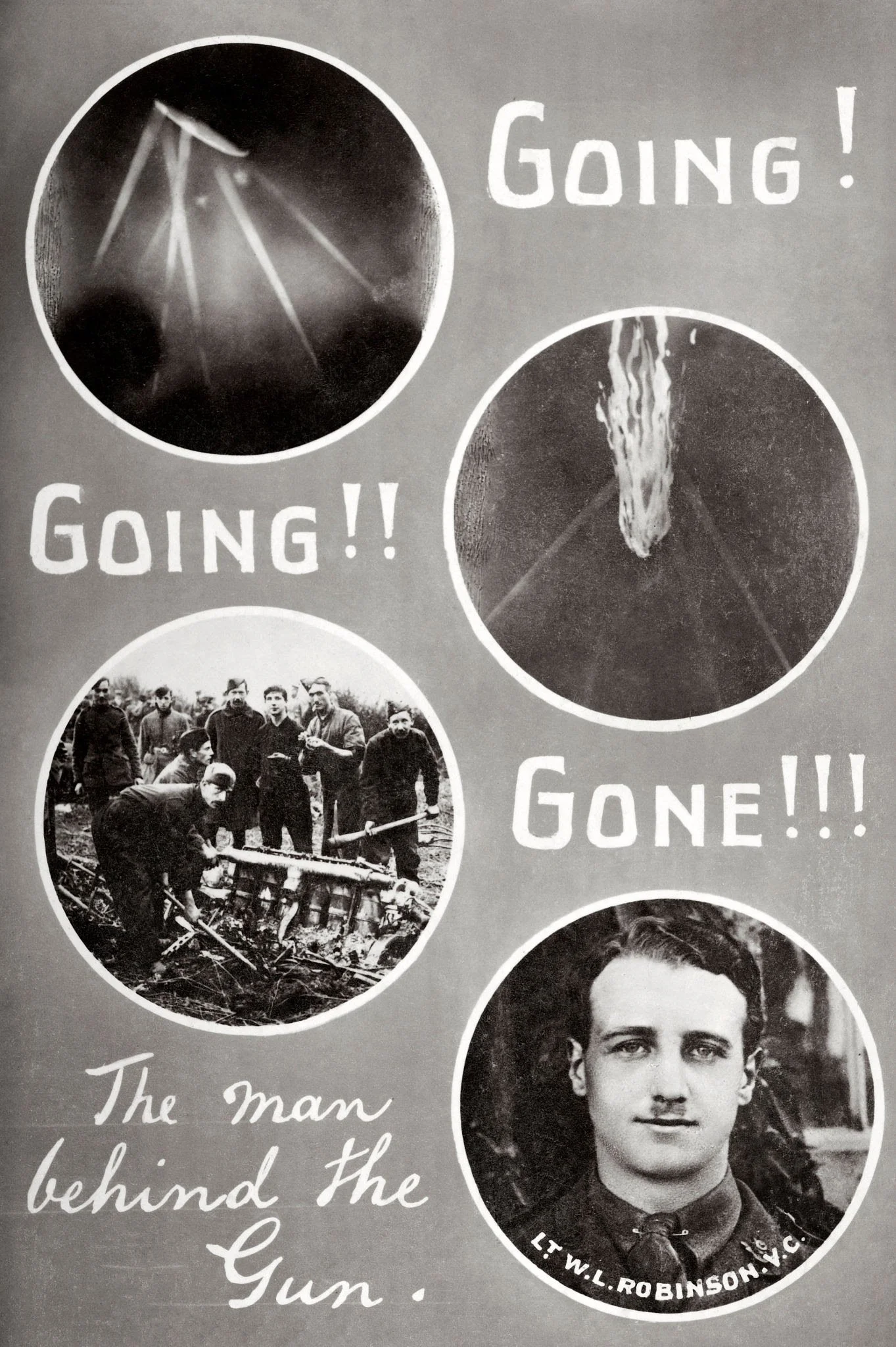

A 21 year old pilot who shot down a zeppelin over London, Leefe was awarded the fastest Victoria Cross in history. He died of Spanish Flu in 1918.

Thank you for playing Leefe’s trail! You have unlocked recordings, scripts, a mini blog and a downloadable postcard!

Postcard of Leefe, Getty Images, Google.

Listen to Leefe’s formal report.

W. Leefe shot down a German airship over Britain on the 2-3 September 1916. The event was seen by thousands across London and the surrounding counties, making him into an overnight celebrity. Leefe had trained as a Lieutenant at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst and came from a wealthy family based in India. So he was used to making formal reports directly to heads of command, unlike some of the other trail characters.

Listen to Leefe’s letter home.

Although he quickly became a national celebrity, Leefe was still only 21 years old. In this personal letter extract, Leefe describes the above event in more informal and excitable terms. Though he was celebrated as a great hero, shooting down a zeppelin ended up restricting his freedom. Leefe became too valuable for British propaganda and was kept away from the front lines so that the government could continue to use his image to encourage donations and raise morale.

Mini Blog

〰️

Mini Blog 〰️

“Baby Killers”: the impacts of air raids

Exiting from his plane early on the morning of the 3rd September 1916, W. Leefe Robinson could hardly believe what he had just achieved. The zeppelins that had been terrorising the “Home Front” were no longer indestructible.. But this story is not as simple and successful as it first appears.

The arrival of aerial warfare was new and prompted a variety of reactions. For historian Susan Grayzel, ‘the arrival of air warfare blurred boundaries between home front and frontline’, with the German air raids specifically shattering the divide between fronts. This new technology ‘demanded new ways of thinking about the state and the home, producing a newly militarized yet democratic civilian citizen’. Simply put, civilians were not isolated from warfare that had previously relied upon “rules of combat” (at least in certain circumstances). This not only changed civilian identity to one of wartime civic responsibility, but also permanently altered the relationship between the governing state and the individual home.

At the start of the air raids in 1915, most people were curious of the floating airships, standing outside their homes to get a better look. Airships were actually highly inaccurate, yet they were still a foreboding and threatening presence above city skylines. The media leapt on this shocking imagery, highlighting deaths of women and children in particular, stirring up a mixture of panic, shock and anger. Propaganda attempted to channel these feelings into increased recruitment and donations to the war effort and were largely successful. The consensus was still torn on whether to retaliate with air strikes or not, as well as whether to warn the public of possible air raids. While eventually warnings would be given to public places, the matter of retaliation remained a contentious issue. The Times reported in 1915 that the effect of the air raids was ‘not a demand for peace, but a demand of the whole nation to help in the ward’. But protests for peace still continued, with the Daily Herald praising ‘the work of those who were speaking out against reprisals’.

Leefe’s destruction of one zeppelin would not end the war, nor would it stop air raids. But it was highly significant for public morale to create a British hero as the war dragged on. As a young pilot with an upbringing in British colonies and military colleges, Leefe made an ideal candidate for this role of “national hero”. National heroes may have raised morale, but they also heightened the nationalistic emphasis of public discourse. The medical journal, The Lancet, for example, argued that British people had ‘British phlegm’ that made them hardier and calmer. On the ground, there was a growing idea that only certain groups panicked under fire, especially targeting Eastern Europeans, Jews and Arabs. Germans living in Britain were often targeted more aggressively, with German-owned businesses attacked after bad air raids.

As Leefe returned in 1919 after a year as a prisoner of war, Britain had undoubtedly changed. Its populace had experienced warfare in one way or another, and many sought more rights and representation as a result. Leefe, however, fighting Spanish Flu in a cold winter, would not live to see it.

Portrait of Leefe, included on the frontpage of War Illustrated