Vera Holme/ The Nurse Driver!

Vera or “Jack” to her friends and lovers was an actress and suffragette originally from Southport, who became Emmeline Pankhurst’s chauffer in 1909. She started a relationship with Eve Haverfield, a fellow suffragette and philanthropist, and joined her in establishing the Women’s Volunteer Reserve.

The pair spent most of the First World War in Serbia, working for Elsie Inglis’ Scottish Women’s Hospitals. The pair were briefly held as prisoners by the Germans and Austrians. Vera helped smuggle a message out of Russia to Britain, ensuring that Serbian troops were pulled out of the worsening conflict.

Thank you for playing Vera’s trail! Access sound clips, a mini blog, scripts and your illustrated postcard here!

Listen to Vera’s poem for Eve Haverfield, written in 1909.

In the early days of their relationship, the pair rode around Arthur’s Seat together. They were fond of animals, and kept horses and ponies at their shared cottage: Peace Cottage.

Listen to Vera’s Satire, written while held captive by the Germans.

While many of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals wards had already fled Serbia, some chose to stay behind; this included Vera and Eve. They stayed together with their adopted dogs and mutual friends, each finding different ways to protest. Vera wrote this Satire, while Eve was reported to have insulted the men in German.

Listen to the opening to one of Vera’s lectures.

Based on an extract found in her archive, this speech shows how Vera used her oratory skills to raise funds and awareness for Serbia’s plight in the First World War. Though this is a more serious lecture, she was also known to regale audiences with amusing tales of her travels. This made her extremely popular, especially in Liverpool where she began her dramatic career.

Listen to extracts from Vera’s diary

Eve died while working at an orphanage she established to care for those left parentless in Serbia after the conflict. Vera visited her grave there for months, taking care of the orphanage before leaving for Britain in the early 1920s. She spent the rest of her life with two women in Scotland, where they later became known as the Ladies of Lochearnhead.

Mini Blog

〰️

Mini Blog 〰️

“Twin Souls”: a queer history of the Eastern Front

For historian Jane Marcut, ‘the Eastern front is the female ‘other’ of World War 1’. While Serbia was not considered strategically valuable to the Allies, women like Eve and Vera (members of independent women’s aid organisations), made it the heart of their operations. As the British government had initially turned down their help, it was only natural that they set their sights elsewhere. Dr Elsie Inglis, the founder of the Scottish Women’s Hospital, was even told to “go home and sit still” by the War Office after she offered them aid; her organisation would send 14 teams across Europe.

The makeup of the teams varied, but the majority had one key commonality: they were involved in women’s suffrage. Vera “Jack” was Emmeline Pankhurst’s chauffer and took part in marches across the country, while Eve, with her gentry upbringing and military background, took on more leadership roles – as well as punching policemen in the face on more than one occasion. The Scottish Women’s Hospital itself had been founded through support from the NUWSS, another women’s suffrage organisation, even including their symbol on ambulances and pamphlets. Unlike the VAD nurse or the “munitionettes”, then, the groups that Vera and Eve moved in had a distinctly rebellious edge. Some of these women were trained doctors, riflewomen or leaders, while others adapted to whatever was required of them. Historian Angela Smith claims that this flexibility made the Eastern Front, Serbia in particular, ‘the ideal theatre of war’ for these women. They had more authority over their units and were sometimes ‘assumed by the local population to represent their nation’, turning some of them into unofficial diplomats. This meant that Eve and Vera met with local leaders, ranging from Colonels to Duchesses, and sometimes overruled existing organizations.

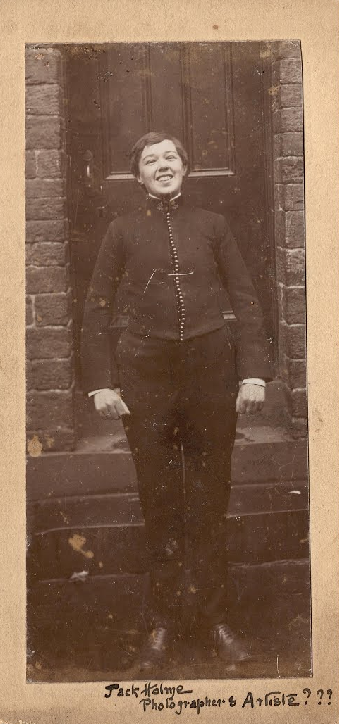

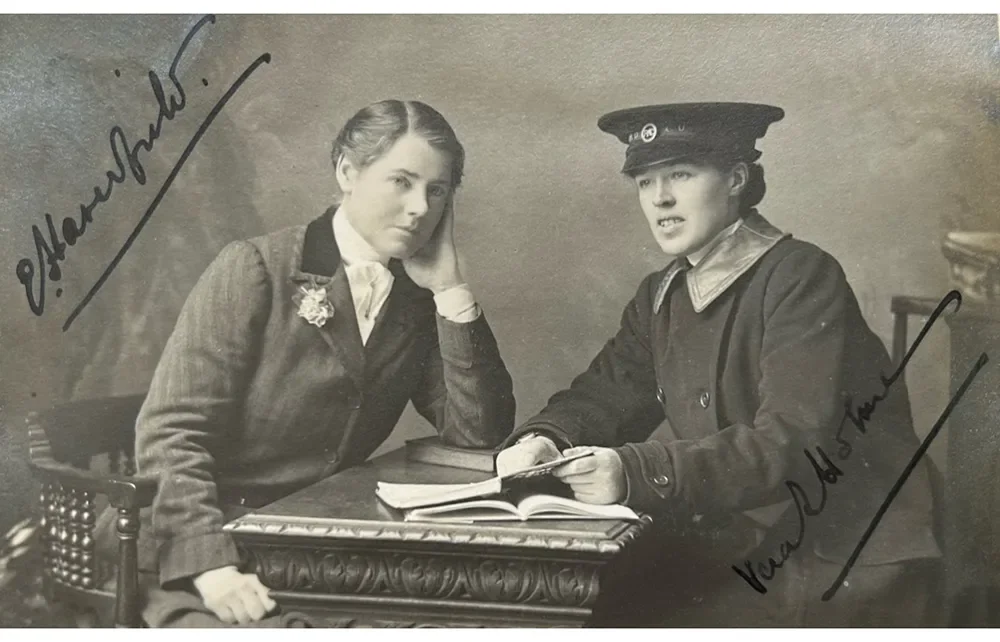

The couple’s relationship, especially amongst the women in their unit, seems to have been an open secret. Vera “Jack” wrote love poems to Eve, they had their initials carved on their shared bed at home, and they were often inseparable. Vera seems to have gone by both names, Vera and Jack, and enjoyed dressing in more masculine attire. When the pair moved to Lazarevac, she wrote that she had adopted a ‘full Serbian man’s kit’ and cut her hair short, much to Eve’s approval: ‘I look like an impresario, Eve says, and she loves it’. Many of the pair’s friends and unit were also involved in queer relationships, such as Edith Craig, the actress, and Elsie Inglis, the founder of the Scottish Women’s Hospital. Other women’s diaries described Eve’s attractiveness and interest, while others noted Jack’s flirtatious nature and the fact that she wore a gold pinkie ring given to her by an unknown lover.

As the pair reached Russia, there was another change in the Hospital’s dynamic between the drivers and nurses. The transport units, in their Khaki suits and short hair, were nicknamed the “Buffs”, while the medical units were called the “Greys”. The Buffs enjoyed showing off their physical prowess in tug-of-war matches, alongside smoking, fighting and flirting, causing more than one crew member to write ‘one wonders what sex they are’. Though “Butch” and “Femme” identities would later become a mainstay of lesbian bar culture from the mid 20th century, the dynamic between the “Buffs” and “Greys” show how queer people in the past played with gender conventions in different contexts. Historians of war have argued that ‘war desexes men and women’, yet in Jack and Eve’s circles, this binary is exposed as playful, changeable and seductive, even under the shadow of war.

Vera “Jack” Holme in 1902, dressed as a bellboy

Vera “Jack” Holme and Evelina Haverfield, sitting for a studio portrait