Jack & Alice “Lily” Cornwell / The “Boy Hero”

Jack was only 15 when he joined the Royal Navy without his father’s permission, keeping in contact with his mum until joining the crew of the HMS Chester. During the Battle of Jutland, the largest naval battle of the First World War, Jack was gravely injured standing at his post amidst shell fire. He died aged 16.

Alice “Lily” collected Jack’s Victoria Cross, but did not receive a portion of the fund set up in her son’s name. As we do not hear from her in the archive, short parts of her voice lines are not from primary sources. The letter and news report she reads, however, are genuine sources.

Alice died in poverty in 1919, having lost a son and her husband. Jack, meanwhile, became a famous “Boy Hero”, still celebrated in the Royal Navy and the Scouts.

Thank you for playing Jack & Alice “Lily’s” trail! Access sound clips, a mini blog, scripts and your illustrated postcard here!

Extract Script for Alice “Lily” Cornwell

Listen to Alice “Lily” read Jack’s letter, written in early 1916.

This letter was written during Jack’s training at Plymouth and gives insight into his busy family life, with many siblings, chickens and cats. We do not have letters from Alice, so her introduction is based on contextual information from the letter. * Constriction= Conscription in the letter.

Listen to Alice read an extract from The London Gazette, September, 1916.

We know that Alice “Lily” collected Jack’s Victoria Cross at Buckingham Palace, but we do not have her written perspective of events. The Boy Cornwell Memorial Fund was set up to support disabled sailors as well as Cornwell’s family, but Alice was left behind, dying in poverty in 1919. The rest of the family eventually emigrated to Canada. What do you think of the voice actor’s interpretation of Alice’s feelings?

Mini Blog

〰️

Mini Blog 〰️

Constructing a “Hero”

Writing in The Guardian, Dr Rupert Gude stated that ‘it is extraordinary that 100 years after young Jack Cornwell was mortally wounded in the Battle of Jutland, we still cannot admit that there is no eyewitness account that he did anything brave.’ Indeed, on making this project, it was surprising how few sources I could find for Jack and his experience of war – this is why connected sources are “read” by his mother, rather than himself. Even his portrait was staged by his brother, likely following his death. So, we have a faceless hero who somehow became the face of the Royal Navy and the Scouts, with no confirmation that he ever ‘did anything brave’. How did this happen?

The First World War is mainly remembered as a land and air war, with images of the “Tommy” and pilot remaining iconic in film and TV. But naval battles were just as crucial. Britain needed to maintain its naval blockade against Germany, to prevent further attacks from sea as well as air. Germany, meanwhile, was attempting to draw out British ships to break this blockade. It all came to a head at the Battle of Jutland, the largest naval battle of the First World War, where dreadnoughts would clash for the first and only time. The conflict involved 100,000 men and 250 ships and was generally considered a confused mess. British codebreakers had informed the navy of an ambush, yet they still lost 14 ships in the opening confusion. Once the main fleet arrived, the Germans retreated. This was not the decisive and uplifting victory either side had hoped for.

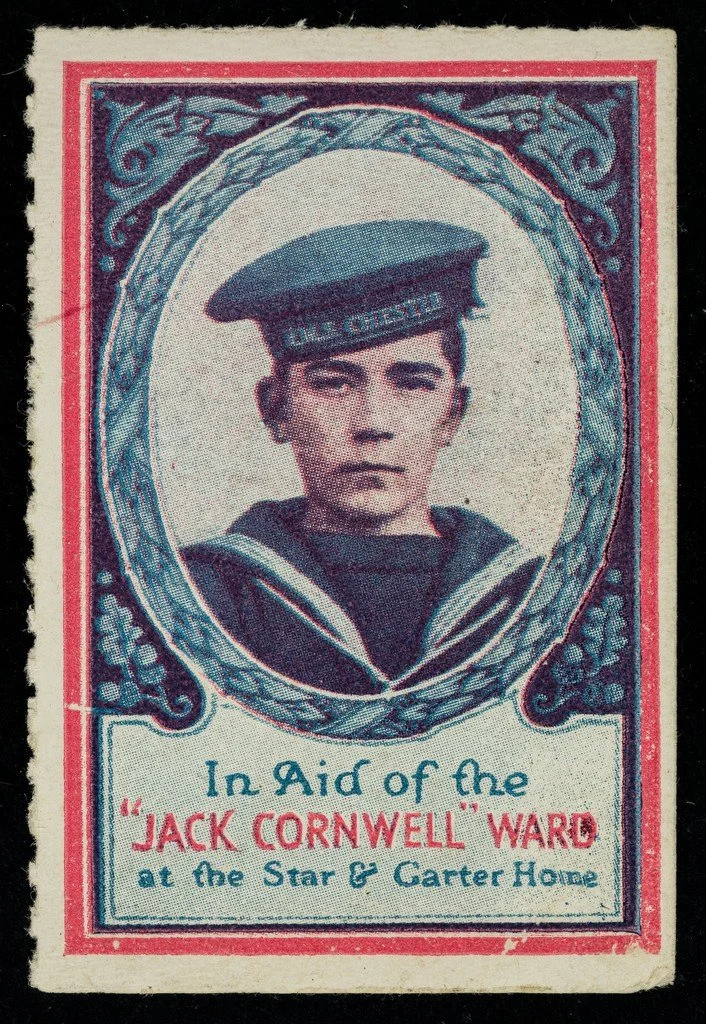

Jack’s ship, the HMS Chester, was caught in a crossfire as it went to investigate the gunshots. He died after receiving shrapnel to his stomach, leaning at his post. He was initially buried in a pauper’s grave, as the family could not afford an extravagant burial. Only after he was buried, however, did he draw media attention. While Leefe’s identity as a colonial gentleman suited the British media as a contrast to German “Baby Killer” zeppelins, Jack was a great example that any British man could “do his bit”, regardless of background. Jack was thus reburied with full military honours, awarded the Victoria Cross and had his image plastered over stamps, paintings and newspapers. He still has a Scout badge named after him. Creating a hero like Jack was important to deflect from the confusing nature of the Battle by raising public morale instead of raising their indignation. With both the Germans and the British claiming the Battle of Jutland as a victory, Jack’s image was more important than ever.

As for Alice “Lily”, who leads a lot of this trail, her personal opinions on the Battle are unclear. There is evidence that she and Jack communicated regularly, and that she collected his Victoria Cross, so the pair had a close relationship. She also attempted to see him in hospital, but he died before she could reach him. Her voice does not appear in the collections, and mothers like her are often avoided in discussions of war except as an archetype. Unlike the other women from the trails, she was not involved in wartime nursing, reserve forces or munition work, nor was she contacted for comment about her wartime experience. She steps out of frame, and we hear nothing until her death certificate. The “Boy Hero” story, therefore, could encompass more people than Jack and Lily, it also stretches to include Admirals, the War Office, painters, journalists, stamp-makers and more.

Painting of Jack, displayed at the Royal Navy training base.

Frontpage of The Daily Mirror, July 1916.