Caroline Webb (later Rennles)/ Munitionette

Caroline was a working-class woman from Camberwell who worked in various munitions factories during the First World War. When at the Slade Green Factory, her skin and hair turned yellow from using TNT without proper protective gear.

She later worked at the Woolwich Arsenal, making shells and ammunitions. Here, she became an active trade union member, fighting for fair wages and a safer working environment. After the war, she took part in unemployment protests.

Thank you for playing Caroline’s trail! Access sound clips, a mini blog, and your illustrated postcard here!

Listen to Caroline describe the effects of TNT on her appearance.

Timestamp: 7.02 mins. In this podcast from the Imperial War Museum, Caroline recalls the effect of TNT on her skin and hair, and the mixed reactions it caused from the public.

Watch the medical examination video.

Official videos like these were played in cinemas to reassure the public about the safety of women’s work in munitions factories. Women had been working in factories throughout the nineteenth century, but the hard, dirty and mechanical work of the metal industries was male-dominated until the First World War.

Listen to Caroline describe the health and safety in the munitions factories.

Time stamp: 7.15-8.40.

Though official videos presented factories as clean, orderly and enjoyable places to work, Caroline recalls workplace accidents that were quickly covered up.

Mini Blog

〰️

Mini Blog 〰️

Munitionettes at work and play

By 1918, estimates historian Angela Woollacott, one million women worked in munitions factories. This makes it significantly more populous that other women’s groups, including nurses and other aid. They produced some 80% of ammunition by June 1917, making them indispensable during the First World War. But who were these women? What did their lives look like?

In her interviews, Caroline provides several anecdotes, giving us insight into the life of a “munitionette”. The work was hard, with long hours and few breaks, not to mention dangerous enough to cause serious injury. While munitions and engineering were male-dominated environments, many of these women were not unused to dangerous workplaces. The last century had seen factory production revolutionise how and where people worked, with many women working in large mills and factories, or producing matchboxes and envelopes, or hemming at home in “sweated trades”. Otherwise, working-class women were employed in service, sometimes living isolated and strict lives. As Deborah Thom argues, the change in women’s work during the First World War was less about ‘novelty’ and a radical improvement in ‘the capabilities or skills of women’, but rather a change in how large groups of women were managed. Caroline, for example, worked under Lilian Barker, a pioneer for women in engineering. She also remembered being encouraged to join a local trade union by male workers, where she became an active member from the age of 18. Were women entering male-dominated fields? Certainly. But was this a complete transformation for the lives working-class women? Not quite.

Where change was happening, however, was in the social life of munition factories. The Ministry for Munitions encouraged exercise, games and dancing for the women in their factories, citing health and morale as key reasons. These were not new inventions, however, as factory owners had previously encouraged male employees to form cricket and football teams. This created a shared camaraderie and a loyalty to their factory, many of which gave their names to the earliest football teams like Arsenal and West Ham. Munitionette football teams were immensely popular, with top teams like the Dick Kerr FC from Preston and the Sterling Ladies FC from Dagenham drawing large crowds. Their matches helped raise money for wounded soldiers, thus gaining early support from the FA. Players from the Sterling Ladies FC were nicknamed the “Dagenham Invincibles” as they never lost a match, while Dick Kerr FC won 746 out of 800 games. Women’s football had been gaining traction for years before 1914, but by 1918 it had become a country-wide spectator sport.

After 1918, however, attitudes surrounding women’s work and play was changing. This was not the sudden removal of all women from manufacturing and sports clubs as sometimes portrayed, but women’s freedoms were changing. In 1918, women over 30 who reached a property qualification were granted the vote, while working-class women saw their football clubs banned and places of work close or alter. In 1921, the FA banned women’s football, declaring it ‘unsuitable for females’. The ban would not be lifted until 1969.

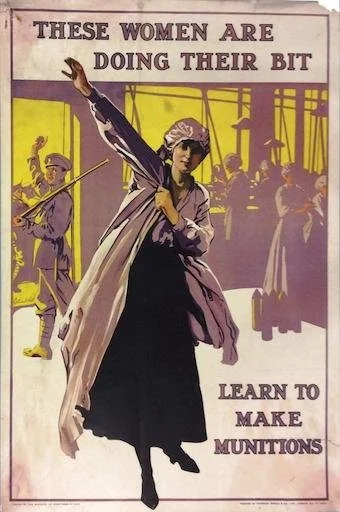

Propaganda Poster for munition workers.

Sterling Ladies FC, AKA “The Dagenham Invincibles”